It is said that tea was introduced to Japan from China during the Heian period (794-1185). While tea-drinking culture was enjoyed by nobles and monks, tea was consumed less as a casual beverage and more in the manner of a medicine, due to the stimulating effects of caffeine. After Zen monks brought tea cultivation from China to Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333), the tradition of tea drinking spread to the samurai, members of the military class, as well.

Beginning in the latter half of the Muromachi period (1336-1573), a tea-tasting contest called tōcha became a popular gambling sport among the samurai, who were known for flamboyant behavior. Participants would attempt to guess the brand of tea they were served while engaging in other frivolities, such as collaborative poetry (renga) at clubhouses, or kaisho. While the clubhouses weren’t used exclusively for this purpose, they nonetheless were the first Japanese teahouses.

Later, a parlor tea (shoin no cha) tradition began with the development of traditional residential architecture (shoin-zukuri). But starting in the late 15th century, Murata Jukō and Takeno Jōō introduced a new style of tea ceremony known as wabi-cha. This “thatched hut” or “rustic” style of tea sought to offer a taste of the rural in an urban space.

It was the wabi-cha tradition that Rikyū perfected in the latter half of the 16th century, solidifying the development of this Japanese art. The small buildings and spaces that Japanese people envision when they hear the word “teahouse” come directly out of the thatched hut tearooms of Rikyū.

Basic Components of a Traditional Teahouse

Teahouse garden (roji). In front of the traditional teahouse is a garden referred to as theroji. Guests traverse it on a path of steppingstones, admiring the plants and trees before washing their hands at a stone basin in preparation for entering the teahouse building.

Passing through this natural area outside the building offers a pleasant means of approaching the otherworldly space that constitutes the tearoom.

The host of the tea gathering uses a different, normal-size entrance, called thesadōguchi.

While there are various stories surrounding the origin of the nijiriguchi, it is thought that, since the small entryway would force even a great general to leave his sword at the door to pass through, the space inside becomes detached from reality. Guests move beyond their respective social statuses and interact as equals. It’s also said that entering through such a small door makes the space of the tearoom itself feel larger.

Smaller tearooms are calledkoma, and larger rooms are called hiroma. This room is a nijō-nakaita koma (two mats and a stove hole). Even this small tearoom can hold a tea gathering for three guests and a host.

Stove (ro). From November through April, a stove installed in the tearoom floor by cutting a piece of the tatami is used to boil water. From May through October, the stove is covered back up with tatami, and a portable stove, called a fūro, is used instead.

Alcove (toko). This is a nook or alcove in the tearoom decorated with hanging scrolls and flowers. When guests enter a teahouse, they first proceed to the alcove to admire the decoration. Toko are composed of an alcove post (tokobashira), lower alcove trim (tokogamachi), companion alcove post (aitebashira) and upper alcove trim (otoshigake). It’s not uncommon to spend years collecting pieces with the right history and character to suit these areas.

The wall of the alcove is plaster, and sometimes a window (shitajimado) that reveals the lattice framework of the walls may be opened on one of the side walls. The floor of the alcove may be wooden paneling or tatami.

Washing room (mizuya). This is where the host cleans utensils and makes preparations for a tea gathering.

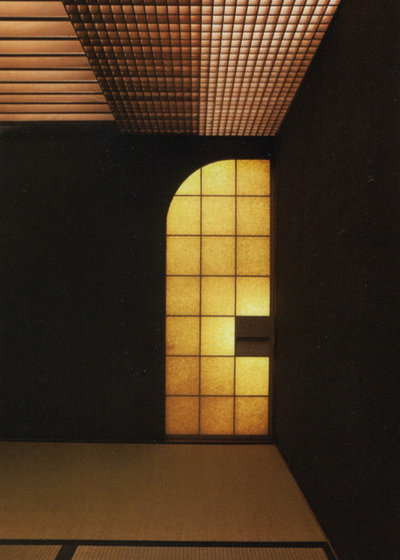

Architect Yasushi Iwasaki ofIwasaki Architecture Laboratory, which produces large numbers of residential tearooms, says, “The chashitsu is truly the product of all of the traditional Japanese crafts combined. Rather than calling it a work of architecture, it may as well be called the largest of the tea utensils.” Iwasaki designed the teahouses in the previous three pictures.

In explaining his tearoom designs, Iwasaki says, “Many of my clients who appreciate the tea ceremony decided they were interested in holding their own tea gatherings, but there have also been a few individuals who were interested in having their own teahouse because they wanted to learn the tea ceremony.” Tea gatherings include a traditional meal (kaiseki), thick tea (koicha) and thin tea (usucha).

In modern Japanese cities, many people don’t live in stand-alone houses but rather in housing complexes. Tearooms sometimes are created in these complexes too. One example is this Tokyo tearoom designed by Hiroyuki Suzuki of Atelier 137, which has fulfilled the dream of his client’s wife, who has studied the Urasenke school tea ceremony for 30 years.

Installing a tearoom in a housing complex is no simple task. To cut the hole for the stove and meet fire-safety regulations, there needs to be a sufficient amount of space beneath the floor. The washing room must have a water supply and drainage, but because apartment buildings have a predetermined pipe shaft system, there’s little flexibility.

To combat these issues in this apartment, the tearoom area was raised about 16 inches above the rest of the living area.

The floor of the mizuya is equipped with a bamboo drainboard that allows water to flow freely. In anticipation of splashing, the dark blue wainscoting has been switched out for planking at the edge of the pillar. The faucet, dish drainer and shelves are in keeping with Urasenke school sensibilities.

“Because the mizuya is where the washing machine used to be, we were able to set up a water supply and drainage system with no issues,” Suzuki says.

Today’s Teahouses and Tearooms

So far we’ve covered only traditional teahouses and tearooms, but as long as the basic requirements are met — that “the necessities for tea ceremony are provided and the atmosphere of tea ceremony is attained,” as Nakamura says — it’s natural that chashitsucan just as easily be contemporary designs.

The second floor — which constitutes the polyhedron portion of the building — functions as a dedicated studio and tearoom for the owner, a busy lawyer who also devotes himself to painting and the tea ceremony. In other words, the first floor is an everyday space, and the second floor is an otherworldly space.

Facing the entrance of the polyhedron, the studio is on the left side, while the guest entrance to the tearoom is on the right.

In addition, one of the polyhedron ceiling surfaces can be opened, causing light to fall only in the vicinity of a tea gathering’s host, creating a beautiful contrast between light and shadow.

Yokogawa, who has designed a number of contemporary tearooms, not only in private residences but also in public buildings, says of the modern tearoom: “Form is important, but if you get overwhelmed by it, you can’t do anything interesting. Rikyū is the one who established the tea ceremony with its chashitsu and tea gatherings as we know them today, and his success was in being creative and novel for his time. I think the truechashitsu of modern times are those that bring a Rikyū-esque spirit and creativity to the contemporary living space.”

See more of this house

However, traditional Japanese architecture is composed only of a ceiling, supports and a floor — not walls. Interior designer Uchida Shigeru was interested in the idea that “the appearance of walls [due to Rikyū’s chashitsu] was a revolutionary upset in Japanese architectural space,” and set out to directly oppose Rikyū with a series of tearooms with see-through walls made of bamboo and washi (Japanese paper). They are called Ji-An (Retreat of Vedanā), Gyo-An (Retreat of Saṅkhāra) and So-An (Retreat of Saṃjñā).

Since their first exhibition in 1993, they have been purchased by various benefactors of the arts, beginning with The Conran Foundation, and are used for tea gatherings at events.

- Having the individual as its core, chashitsu is the inversion of large entities, such as the time period, society and the world at large.

- Chashitsu explores the ultimately essential, minimal unit of architecture in a closed, small space with fire introduced in it.

- This ultimately basic, minimal unit architecture is a DIY project.

- For the reasons above, the exploration of chashitsuarchitecture is a universal challenge for humanity.

With the four ideas above in his mind, he has created teahouses that follow the principles of Rikyū’s chashitsu: minimization, the introduction of fire (via the stove),nijiriguchi, freedom of design and natural materials. They also incorporate elements not found in Rikyū’s work, such as a view and the abolition of the decorative alcove.

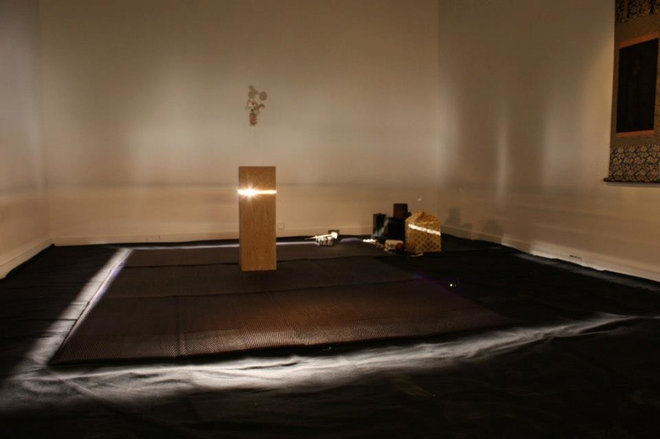

It was built as an installation for a New York art gallery hosting a prehistoric Japan-themed exhibition highlighting the places that people gather in and the spaces that are created not with matter, but with one’s mind.

A wooden box placed in the middle of the gallery emits a “light that defines an incorporeal boundary line” to create a “space.” Four sensors measure the relationship between the individuals inside the space in terms of their numbers, distance from one another and movements, and the light adjusts in order to accommodate the guests.

With fire, people gather: Daily life is made possible, and a community emerges. In the Jōmon period, it’s likely that shamanistic rites were performed around fires. The root of human livelihood revolves around a centripetal core of light and fire, and it’s this message that’s communicated in the tea ceremony, as the host bonds with guests while boiling water over a stove and drinking tea.

Although it’s unusual not to have any hanging scrolls, flowers or tatami mats, Yoshioka says, “I thought to look at the true nature of Japanese culture that exists in the realm of the senses. This microcosmic chashitsu space causes an awareness of the present moment in nature, prompting liberation from the physical realm and integration with one’s natural surroundings.”